A strange procession

The English Eerie is way eerier than you think; plus, poo horror in the Village News

Hi, how are you doing? I am, as I type this, liberally spattered with mud.

Welcome to a rainy February edition of Witness Marks. If you’re new here and would like a quick tour of the village (and the newsletter), start by reading this post here.

And in case you missed January’s free post about what really constitutes warm clothes (and other things) in the countryside, you can find it here:

Witness Marks goes out on or around the 15th of each month; in between times you can find me chatting away in Substack Notes. The first part is free, while the second part, the Village News, sits below a paywall. A subscription to that costs £3.50 a month if you pay via Substack Desktop (Apple add a bit on top if you pay via the app); subscribers can also access all the back issues of Witness Marks, AND they can listen to me read out and discuss my first novel, Clay. But if £3.50 feels like a stretch, reply to this email (if you’re reading this in your inbox), or send me a private message on the Substack website. No questions asked.

Having written a book about the joys of walking in the rain, I’m apparently no longer allowed to complain about it. But god, it’s been relentless, hasn’t it? Our fields are either thick with mud, waterlogged or underwater, the lanes are ‘clatty’ and full of hidden potholes, and the field drains, roadside ditches and dykes are running fast and high. My old cottage door is sticking on its wooden sill, I haven’t managed any gardening and the skies for much of the last few weeks have been grey, grey, grey.

It rained the night the dancers came, a thin, icy rain that drifted down from a fathomless and starless sky. Apart from the exterior lights of a pub, and the wavering white LEDs of the torches carried by locals and visitors, it was a cold and pitch-black January night: many – perhaps most? – of the smaller villages in East Anglia have no streetlights, something I have grown to love. Sixty or so people milled around at the crossroads, chatting, wrapped up in coats and scarves and hoods. It was difficult to recognise anyone, or even to tell men from women. There was a sense of anticipation, but also a faint nerviness: even those of us who knew what was coming couldn’t be quite sure of the form it would take. God help the stranger who stumbled across what was coming by mistake.

A dull, repeated drum beat; distant fires. Down the dark hill marched a strange procession, lit by lanterns and flaming torches: stony-faced men in antique costume, women shrouded in black with garlands of twigs and ivy on their heads. The crowd, now silent, parted to let them pass. They took up position, the women grouped silently around their instruments: melodions, recorders, drums, a tea-chest bass. The men stood in a rough half-circle facing outwards, hands behind their backs, outstaring the spectators. It was time for the dancing to begin.

Molly is a form of folk dance peculiar to East Anglia in which farm labourers – lacking employment in winter, when the land could not be worked – would dance in rural villages in exchange for money. Little is known about its original form, and what we have now is based partly on the scant record, the rest drawn from speculation and imagination. ‘Molly’ was once a word for a man who dressed as a woman, and there is always an element of cross-dressing to it; the sense of disguise also extends to facial features, which may once have been blackened with soot and are now often painted grey or dark green. As well as the bearded, dress-wearing Molly there are other obscure roles that lend the spectacle a note of chaos and disorder not unlike the strange symbols that can arise in dreams: a ‘whiffler', a ‘broom man’ and (appropriately enough) an ‘umbrella man’, though he could not keep anyone dry.

The dances themselves are heavy, rhythmic, deliberately ungraceful: this is not Morris, with its bells and whistles and waving handkerchiefs. The dancers’ hobnailed (or blakey-shod) boots strike the ground hard; the ‘box-man’ roams the crowd demanding money and may menace you if you haven’t come prepared. And the strangest thing of all is this: you stand there under the flaming torches, suffering the changeless rain, and you know that by day these men probably work in IT and take their kids to the football at weekends; you know that the black-clad, ivy-crowned women are local artists, or serve on the parish council; you know that the money that’s collected goes to charity and not to buy ale for ploughmen – and yet for an hour or so, as the dancers stamp and the music skirls, it doesn’t feel like that. It doesn’t feel like that at all.

Here’s a nice thing to kick off the news section with: Mr B’s Emporium are taking pre-orders for my new novel, The Given World, which comes out on May 14 – and if you order from them you’ll also receive a free, exclusive, A4 art print. If you think you might want to read The Given World when it’s published, this would be a good place to order your copy from. You’ll also be supporting a bricks-and-mortar indie bookshop: the Emporium is in Bath, and also offers a lovely subscription service.

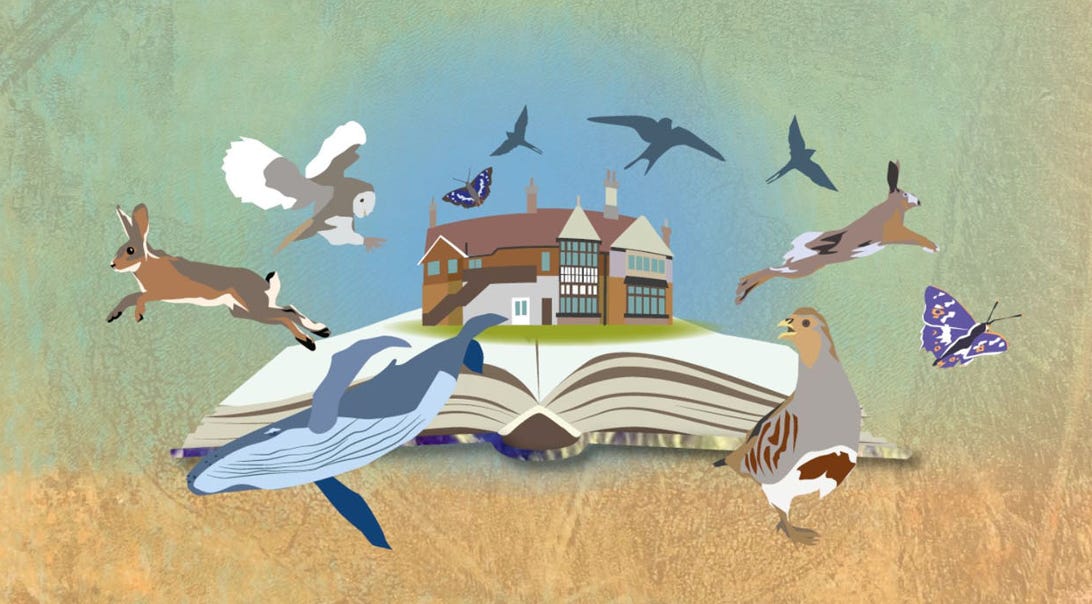

On March 21st (the spring equinox!) I’ll be speaking at Watching Narrowly: Natural History Book Day at The Wakes, Gilbert White’s house and gardens in Selborne, Hampshire. Most readers of this newsletter will already know how much Parson White means to me and how important he’s been to my writing, which makes this event a really special one for me. Best of all, there’ll be lots of other brilliant writers and naturalists there too, including Nicola Chester and Tristan Gooley. Tickets are £50 for a full day’s programme of events, plus access to the house and garden. I think it’s going to be magical.

I wrote for The Times about our local river bursting its banks (as it often does in winter), and about trying and failing to see a congregation of roosting kites. You can read my piece here: it’s sometimes paywalled, sometimes not; or it is for some people and not others. Honestly, god knows.

And for the Guardian I reviewed poet Rebecca Parry’s dazzling puzzle-box of a debut novel, May We Feed The King. You can find that here.

Three things that aren’t on screens

Each month I collect together three things that have interested me, for good or ill, and which can be found in the world beyond your phone or laptop:

👉🏼 A nice thing: Obviously, £6.95 is a deeply offensive amount to ask for a chocolate bar, but having been given some of what’s basically posh crack for my birthday I may now find it hard to go back to my usual Waitrose 49%. Fatso sell the most amazing dark chocolate in chunky bars, with flavours including Morn’n Glory (don’t love the contraction) which is cornflakes, toast and marmalade (!), and Nan’s Stash, which is peanuts, toffee and digestive biscuits (!!)

👉🏼 An interesting thing: The Matthew Strother Center for the Examined Life is a farm in the Catskills where people go to read and talk and think together. You don’t get a certificate, you don’t get grades: it’s not about achievement or prestige, it’s about depth, meaning and purpose. It sounds like utter heaven to me. The closest we have here is the wonderful Gladstone’s Library in Wales, where I’ve stayed several times (including as a writer-in-residence), but the Matthew Strother Center is more structured in what they offer. Applications for three fully funded, week-long retreats in June close on February 22. If accepted, you’d just need to cover your travel.

👉🏼 A thing that made me go ‘hmm’: Cambridge Botanic Gardens is using AI to allow visitors to have “conversations” with plants in the Glasshouse. Per the blurb, “Talking Plants invites you to take part in a live experiment exploring how artificial intelligence can help us connect more deeply with the plant kingdom.” Per me (after screaming into a cushion in several registers): IT REALLY CAN’T, because a) learning ≠ connection and b) you can’t connect with a plant via a chatbot because PLANTS AREN’T CHATBOTS and CHATBOTS AREN’T BEINGS OF ANY KIND. I find this idea so utterly wrongheaded it’s given me a migraine.

That’s it for the first, free part of this issue of Witness Marks; below the paywall you’ll find the Village News, including poo trauma, eldritch scarecrow, Boney the local scoundrel and an unexpected sinkhole – all for just £3.50! A bargain, if you ask me.

If you don’t want to subscribe but you’d still like to support my various endeavours, you can leave me a tip by going here. Thank you – and see you next month!